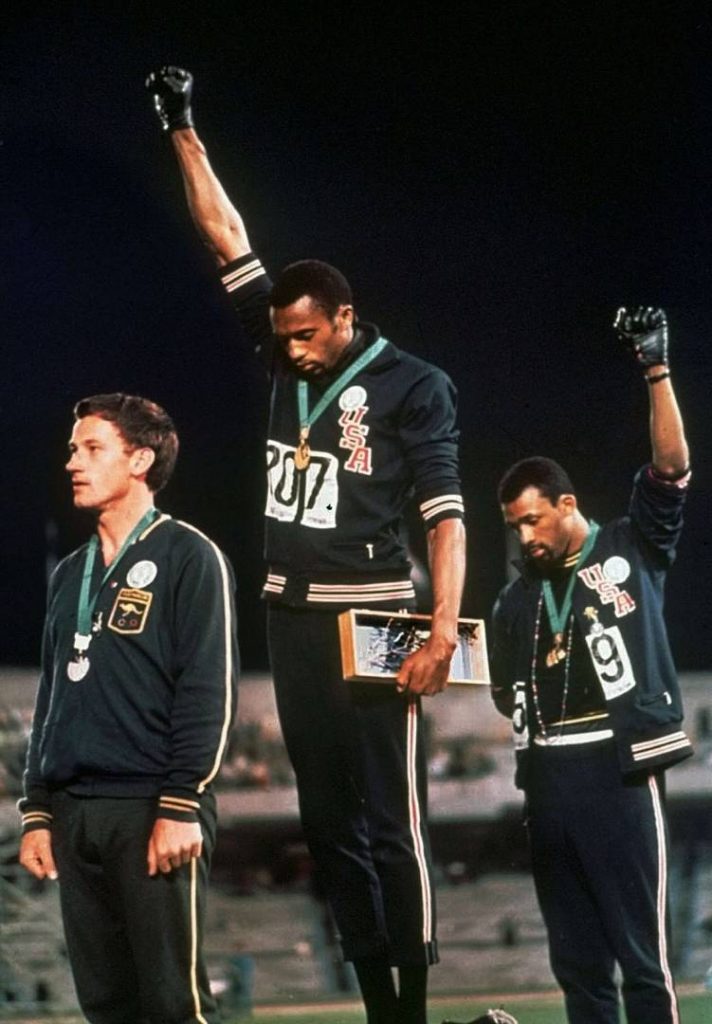

Remembering Peter Norman – Forgotten White Athlete In Black Power Salute That Stunned World And Changed Sport

June 22, 2018

With the 50 Year Anniversary of the famous Mexico Olympic Games Black Power Salute looming, Michael Pirrie pays tribute to Peter Norman, the often forgotten white athlete in the iconic Black Power protest and photograph who has been honoured with a posthumous Olympic Order of Merit by the AOC in Melbourne, and explains why the Salute continues to move and fascinate audiences globally.

Fifty years on, the often forgotten man at the centre of one of the most controversial, dramatic and transformational moments in the history of the modern Olympic Movement and world sport and photography is finally getting the recognition he deserves.

The approaching anniversary of the Mexico 1968 Olympic Games is also bringing greater awareness of the impact and legacies of the famous black power salute that stunned the world, and the personal toll on the three athletes involved in a cautionary and inspiring story of the changing role of Olympic athletes and sport in modern society.

The Black Power salute has left a defining global legacy linking sport with human rights, and connecting the Olympic Games and sport with politics and social change in popular culture forever, including in more recent times the IOC’s own refugee athletes support programme.

The salute has also come to define the unique power of the Olympic brand, with the black US athletes involved, when questioned why protest at the Olympic Games, responded by asking ‘if not at the Olympic Games when the whole world is watching like a moon landing, then when.’

SALUTE THAT CHANGED LIVES & SPORT

The salute heralded a new genre of sport and role for athletes as activists and advocates for change, and paved the way for sport-related campaigns and events associated with social justice.

Recently, these have included American professional footballers kneeling during the national anthem to protest against racial inequality and police brutality in the Black Lives Matter campaign.

While most attention has focussed on the two saluting black US athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carols, who finished first and third respectively in the Mexico 200 metres sprint final, the identity, role and impact of the white athlete in the salute, the Australian sprinter Peter Norman, who won Olympic silver, is still not widely known, publicised or appreciated.

FORGOTTEN OLYMPIC HERO

While a landmark in sports photography, the Black Power Salute has also become an iconic image in wider popular culture, and would not look out of place on the sleeve of a Beatles album or cover of Rolling Stone magazine.

The black-gloved protest has also moved beyond sport to become a symbol of racial equality in popular culture, as reflected in the handwear of the late Michael Jackson and other cultural icons, entertainers and performers.

The image is radically different to the message and circumstances it conveys, like Norman, Smith and Carlos at the centre of the photograph.

Compelling and controversial from the moment it was captured on camera, the image threatened prevailing political, social and sporting conventions like no other in modern sport.

Norman’s presence as the white athlete gives the image balance, purpose, and perspective, spanning both sides of the racial spectrum – black and white athletes united in the common cause of human rights and equality.

In many ways, Norman also represented the silent community of athletes back in the Games Village and at sporting venues around Mexico – and around the world – who privately supported the growing human rights movement but were unable or unwilling to take the risk involved in such a public stand.

The salute photograph is in a moral league of its own, a compelling visual statement about social justice, personal responsibility, and moral courage and speaks to audiences and about issues beyond the world of sport as traditionally conceived.

The power of the image and the salute itself still resonate in sharp contrast to prevailing themes and issues in modern day sport including rampant cheating, corruption and consumerism, and the celebrity culture of sport.

Indeed, the image of the trio – Smith and Carlos, heads bowed and downcast, with arms outstretched and hands clenched and covered with black gloves, and standing alongside Norman with a faraway look in his eyes – conveys an almost religious solemnity that portrays the athletes as sporting martyrs about to be sentenced by authorities for a crime against the sporting establishment and society more generally.

At the pinnacle of fame, after years of sacrifice, training and preparation for the Olympic Games and after scaling sport’s highest summit – standing on the Olympic medal podium – Norman, Smith and Carlos committed sporting suicide by choosing to publicise a politically explosive human rights issue inside the Olympic stadium, the centre of global attention, for a cause they believed to be more important than their own careers or a sponsorship deal.

The image’s sombre expression reflects the great turbulence at the end of the sixties following the assassinations of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobbie Kennedy in the same year, while the student deaths in the countdown to the Mexico Games, following protests over Games costs, violently herald the central funding issue that still divides communities and eludes Olympic organisers.

Although hugely controversial at the time, the salute to black power also provided the perfect counterpoint to the most controversial and divisive salute in Olympic history – Hitter’s Nazi salute at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, designed to showcase white supremacy which was blown apart by black US athlete Jesse Owens whose 4 Olympic gold medals shattered the white superiority propaganda with possibly the single most memorable and important athletics performance of all time.

THREE OLYMPIC MUSKETEERS

The 3 Mexico Olympic musketeers pierced the conscience of elite sport and paved the way for generations of athletes to support social and political causes in wider society.

Extraordinarily, many years later, these would include Norman’s Australian Olympic sprinting compatriot, Catherine Freeman, who draped herself in the Aboriginal and Australian flags in a powerful symbol of reconciliation between black and white Australia after winning the 400 metres final at her home Sydney 2000 Olympic Games.

TRUE BELIEVERS, LIKE LIDDELL

Norman was pivotal to the black power protest salute. Smith and Carlos needed the third athlete on the medal podium to support their cause or the salute would not work, and in Norman, they found a true believer.

Like the legendary Scottish sprinter Eric Liddell, immortalised in the Chariots of Fire movie of the 1924 Olympic Games, Norman was also a devout Christian, and like Liddell, believed in God and in running for a higher cause and in helping others, including his fellow athletes whose beliefs in human rights he also shared.

Although he did not salute, Norman was no protest prop, and even helped to choreograph the salute, suggesting that Smith and Carlos share the black gloves used in the salute after Carlos left his pair in the Olympic Village.

Norman’s strong Salvation Army family background no doubt played a key role in his stand, along perhaps, with unease over the White Australia immigration policy and his nation’s difficult relationship with indigenous aboriginal people.

Norman’s involvement in the black power salute was also groundbreaking for his home nation, helping to widen and deepen international perceptions of Australia beyond that of a passionate and powerful sporting country to one that also wanted a voice and involvement in the political and social revolution that was sweeping the west.

A NATION SAYS SORRY

The trio helped each other survive the fall out from the salute and formed an unbreakable bond of friendship and respect – Smith and Carlos gave eulogies and were proud pallbearers at Norman’s funeral service in 2006, and have since dedicated themselves to keeping Norman’s memory and legacy alive.

While Australian sporting officials have disputed claims that Norman was poorly treated, Australia’s Federal Parliament took the extraordinary step in 2012 of issuing an unprecedented posthumous formal apology to Norman on behalf of the nation.

The nation’s apology to Norman, in part, recognised “the powerful role that Peter Norman played in furthering racial equality,” and also apologised “for the treatment he received upon his return to Australia, and the failure to fully recognise his inspirational role before his untimely death in 2006.”

The storm clouds from the black power salute have also overshadowed Norman’s outstanding record as one of Australia’s finest sprinters – the US Track and Field Federation nominated the day of Norman’s funeral as “Peter Norman Day.”

A five times national 200 metres champion, Norman’s heat-winning time in Mexico (20.17 secs) was briefly an Olympic record, while his silver medal time (20.06) in the 200 metres final set an Australian and Oceania record – a record that still stands today as an enduring statement of Norman’s great speed and running ability.

The failure to celebrate and promote Norman’s Mexico sprinting achievements in Australian media, schools, sports centres and wider community may have robbed Australian sport of vital momentum, energy and profile needed to nurture sprinting excellence, and weakened Australia’s sprinting culture.

NORMAN’S LESSONS & LEGACIES

While Norman’s many admirers will welcome the recognition from the AOC’s Order of Merit and other gestures of appreciation championed by AOC President John Coates, there is disappointment also that much more was not done much sooner while Norman was still alive to know of the high regard in which he was held across the sporting world and beyond, especially in his own country.

There has also been talk of a statue for Norman, and perhaps the ideal location for such a tribute should be outside the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the site of the posthumous Olympic Order of Merit ceremony for Norman, and the main stadium for the Melbourne 1956 Olympic Games, where Norman’s Olympic dreams were born in the electrifying atmosphere that filled the host city, where Norman grew up and started sprinting in a pair of spikes borrowed for him by his father, according to local Olympic folklore.

If properly promoted and communicated, the ideals and goals that motivated Peter Norman and his band of athlete brothers can help to make sport more relevant and meaningful to the lives of young people in today’s equally turbulent times.

Michael Pirrie is an international communications strategy adviser who has worked in senior positions on Olympic and international events, and was Executive Adviser to the London 2012 Olympic Games Organising Committee and chairman Seb Coe. Michael also worked with Peter Norman on the unveiling of the medals for the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games at the Sydney Opera House.